“Understanding Compounding”

by Alexander Smith (WPI)

It seems to me that everyone in personal finance accepts that people underestimate compounded returns. But I’ve never seen data on the topic – data that compares people’s expectations about portfolio growth to what the math tells us will happen. It begs the question: if people underestimate portfolio growth, how big is the bias?

To shed light on the issue, when I recently spoke to a group of students about compounding, I asked them to guess the value to which a portfolio would grow under certain assumptions. Here’s the scenario that I gave them:

“Sally is 25 years old and makes $70,000 per year. Assume that her income increases by 5% per year for 10 years and then 3% per year after that. She always saves and invests 10% of her income. She earns average annual investment returns of 8%. How much will she have when she’s 65?”

Before you read the answer, would you like to guess? Are you curious to see if you underestimate compounding? The answer is $3,252,234.40. Yes, over $3 million.

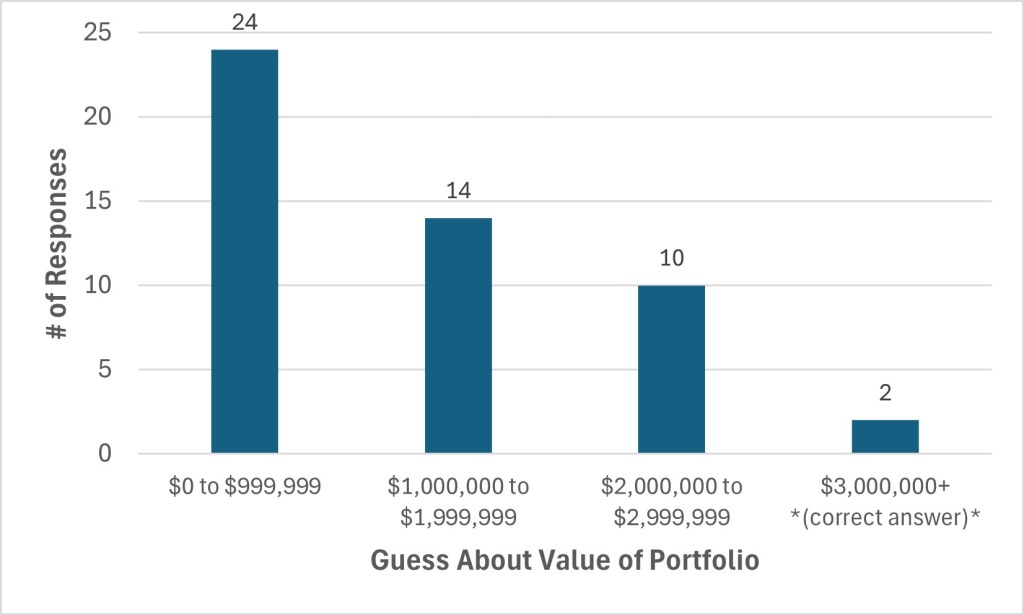

I was speaking to 69 students, and I asked them to volunteer open-ended guesses. 55 of them did, 4 of which were: “a good amount,” “a few million,” “a lot,” and “a lot :)” One of the numerical guesses was $287 quadrillion +, basically digits across the screen. The remaining 50 guesses were sensible, and I’ve graphed them in the bar chart below.

Before I comment on the results, I should say that the students were all undergraduate students, most of them studying engineering. Calculus is required of all of them. They have strong number sense and numerical skills. In that regard, they’re well suited to the task. But they have limited experience (if any) with investing. They’re young.

As you can see from the graph, only two guesses were higher than $3 million (they were both $5 million). The other 48 guesses were all less than $3 million. The average (mean) guess was $1,143,600. The middle (median) guess was $1 million, as was the most common guess (mode).

I was surprised that 96% (48 out of 50) underestimated the power of compounding. 96%! The average guess was just over a third of the correct amount, helped by the two high guesses of $5 million. The middle and most common guesses were less than a third of the right answer. The bias turned out to be larger than I ever would have expected. Now we know.

What are the implications of people’s tendency to underestimate portfolio growth/the power of compounding? My concern is that if they don’t realize how powerful these forces can be, they might not save and invest to the extent that they should. Let’s see what we can do about that!